Duxford Paper Store (2019) 0.03 ach. Photo from Elemental Solutions.

Is Passivhaus Still Relevant?

With heat pumps and a decarbonising grid, is Passivhaus worth the extra effort?

With heat pumps and a decarbonising grid, is Passivhaus still relevant, and worth the extra effort?

We posed this question to our trainer Nick Grant, a sustainable building consultant with a lifelong passion for doing more with less.

Passivhaus – a standard that works

After years of designing and constructing so-called ‘eco-buildings’ I reluctantly embraced the Passivhaus standard because I saw that it worked. Passivhaus represented a significant leap in comfort and energy efficiency, it was a no-brainer, I couldn’t unsee what we had seen working so well in Austria and Germany. That was nearly 20 years ago.

Now people are starting to question whether Passivhaus is still the right target. Some argue that it does not go far enough - but I will focus on the claim that with heat pumps and a decarbonising grid, combined with higher standards for normal buildings, the gap has closed and Passivhaus is not worth the extra effort!

Insulation may have got a bit thicker over the years but has the performance gap really closed and how much extra effort is actually required to achieve Passivhaus. If not doing Passivhaus, what would we leave out? Generally extra effort refers to airtightness and installing mechanical ventilation rather than slightly thicker insulation or better windows. Indeed, once we move beyond detached houses to larger building there is often not much difference between insulation thickness in Passivhaus and standard builds but that is another story.

Early adopters learnt lessons

Our first Passivhaus buildings were certainly a challenge and put us on a steep learning curve, but it had to get easier. As early adopters we wrestled with a complex origami of airtightness tapes and membranes. We reduced thermal bridges by slapping on extra layers of insulation or using expensive thermal breaks. We twiddled the knobs in the PHPP (energy balance spreadsheet) cranking up the glass to the south and reducing it to the north. We then bolted on expensive shading to try and reduce the summer overheating. We didn’t have the experience to know what really mattered so we made some mistakes, sweated a lot of the small stuff and missed some big easy wins.

'Just for fun, testing a 260m2 Passivhaus with a 12V fan with builder Dai Rees. Official test result 0.1 ach @ 50Pa.’ Photo credit: Elemental Solutions.

Airtightness

‘Build tight ventilate right’ is a mantra that few in the industry would disagree with until we get down to numbers and specifics. Then things can get very heated, as this area is still very poorly understood and the idea that airtightness means living in a plastic bag is still going strong.*

Passivhaus airtightness is still seen as the main risk when contractors are pricing. Having struggled to achieve a permeability of say 5 m3/m2.h (m/h for short) a target of 0.6 ach (air changes per hour) seems like a pipe dream. However, because this was a tenfold step change rather than an incremental improvement, Passivhaus pioneers were forced to radically rethink the approach. Rather than adding ever more tape and sealants with diminishing returns, we had to radically simplify the airtightness strategy.

I can remember on my first Passivhaus project (a timber school) being on-site and struggling with a particularly challenging Mobius strip of a membrane detail. As we were scratching our heads bald, Mark Smith, the contractor’s design manager, said that what we needed was a grammar of airtightness. Rather than hundreds of carefully drawn but complex details that would be ignored, we needed a set of simple rules for everyone to learn. Then the whole team could speak the same airtightness language. These rules become second nature and get applied at the earliest stages of design and followed through to final handover.

NOTE (We teach what we have learnt of these rules in the Coaction training).

“Civilization advances by extending the number of important operations which we can perform without thinking of them.”– Alfred North Whitehead

For timber buildings we use the robust racking board we need anyway as the air barrier. Rather than being a disadvantage, the unyielding rigidity of a board rather than a lovely flexible membrane, forces simpler detailing at the design stage. But the board we used as the air barrier turned out to be slightly permeable, enough to account for around half of the total allowable leakage. This was annoying and we reluctantly considered brushing on PVA or using additional membranes. This slight permeability would not have been a problem at 5 to 10 m/h so there had been no reason for manufacturers to improve their product. However, remarkably soon, boards appeared on the market that met the quickly growing demand for excellent airtightness. These boards also had a smoother surface, so were easier to tape. Without such challenging airtightness requirements there would have been no demand for these products.

What is really interesting is that those who have yet to embrace Passivhaus levels of airtightness are already using these premium products as they also make it easier to meet less challenging airtightness targets.

This leads to an interesting situation where people are paying a bit more for the quality airtight products, but the lack of a really ‘challenging’ target means that the lessons of simplified airtightness strategy have not had to be learnt. Poorly planned junctions lead to time consuming additional work on site and perhaps an additional test, which is expensive because of the delays and uncertainty it causes.

And yet contractors working with well-planned designs, building their first Passivhaus have consistently achieved airtightness permeabilities 5 to 10 times tighter than required for Passivhaus, by accident. The site manager for a large contractor was criticised by his boss for wasting time when he greatly exceeded the required Passivhaus airtightness target. His response was to ask if he should drill holes in the airtight plaster layer to make it worse?? Extra time was put into planning the details but then it was just handle turning. The details then got adopted on future projects, again building on experience. It is simpler and cheaper to just design for no leakage than to meet a target.

* m3/m2.h and ach are two ways of representing airtightness of the building, for dwellings the permeability (m/h) is roughly equivalent to infiltration (air changes per hour m3/h.m2*)*

Save money and carbon

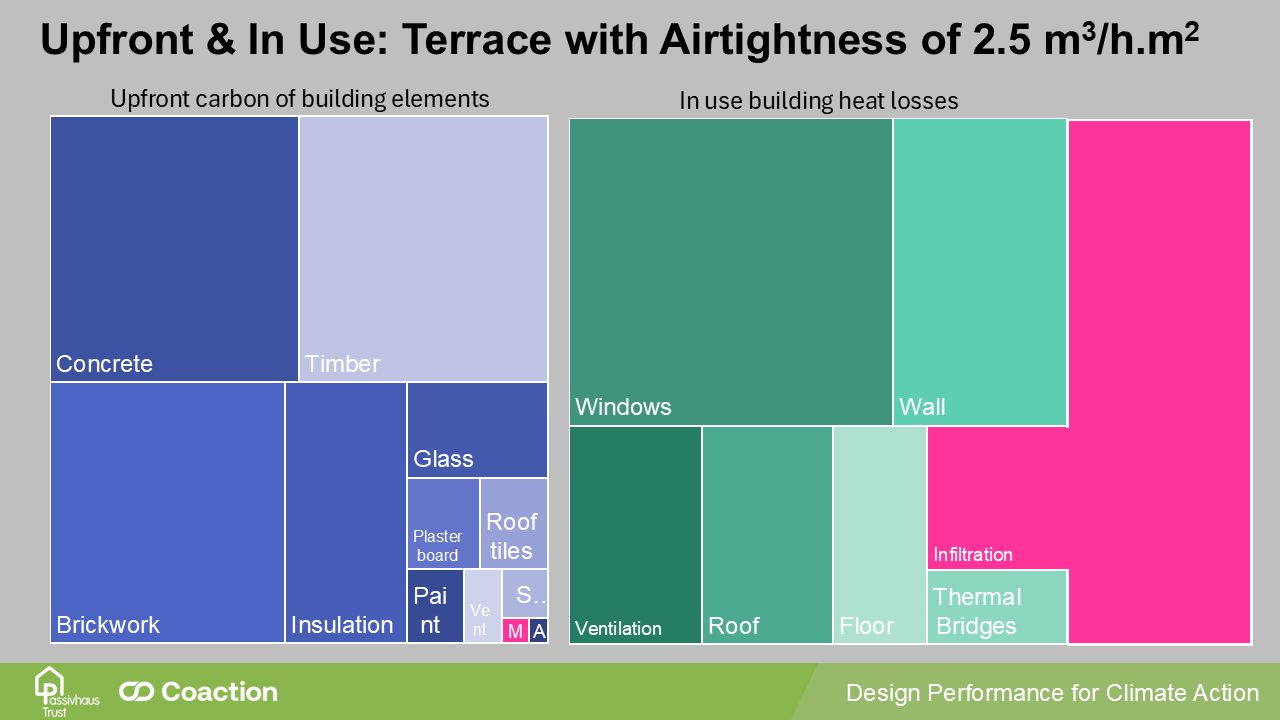

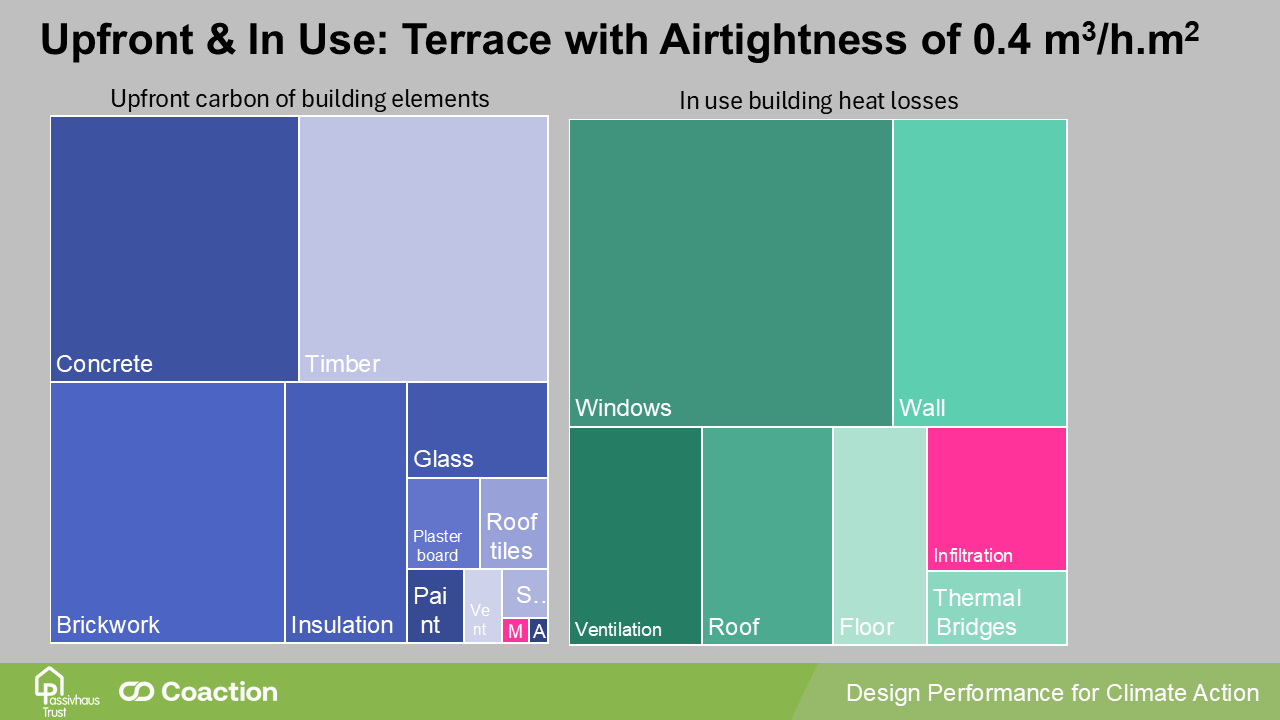

The following graphic is from an excellent presentation by Sally Godber (Ref 1). One of the criticisms of using special airtight products is the up-front (carbon) emissions. From her graphic we can see that like the cost, they are minor. But the main point is that if they don’t then deliver the potential saving, we are wasting money and carbon.

(Below > 5 m3/h.m2 @ 50Pa the airtightness materials are the same. So, airtightness of 0.5 and 5 have same carbon footprint.)

Highlighted in pink - Left: M=membrane carbon emissions. Right: Infiltration = heat loss due to air leakage at 2.5 ach compared to heat loss at 0.4 ach for the same upfront carbon! Image credit: Sally Godber

Why not build tight and ventilate right?

If much better airtightness was a requirement, it would become the norm and everyone could stop wasting time arguing about it, including writing and reading this article!! There really are other things I’d rather be doing! At the risk of alienating any libertarians it is a bit like seatbelts and motorcycle helmets; it is a huge issue until it is normal.

There is only one argument I know for not embracing much better airtightness, and it is wrong!

The belief is that if a building has an air leakage greater than around 5 ach at 50 Pa, you don’t need to install a proper ventilation system but can rely on random leakage and trickle vents plus a few cheap but noisy intermittent fans for loos, kitchen and bathrooms, thus saving developers a tiny bit of profit. However, even if we don’t care about heating bills or thermal comfort, personal experience and academic research [Ref 2. Farren et al & 3] confirm that this random leakage leads to poor air quality with serious health risks up to and including premature death.

Once we accept that some form of continuous controlled ventilation is the only practical way to deliver safe indoor air quality, then the tighter the building the better.

For buildings with balanced heat recovery ventilation (MVHR or HRV), even at a Passivhaus qualifying airtightness of 0.6 ach @ 50 Pa (n50), the heat loss due to draughts can still be greater than that from the ventilation system, meaning there are savings to be had by building even tighter.

For continuous mechanical extract ventilation (MEV) without heat recovery we find the energy savings tail off as the building gets tighter than ~3 ach. However, for MEV to suck fresh air into bedrooms and living rooms through controlled inlets, we need a good enough airtightness to create a pressure difference. Otherwise, air is as likely to enter at the weakest points, perhaps through gaps around incoming services in the utility room, with stale moist air exiting by stack effect through the bedrooms. So again, the tighter the better, but for good air quality rather than energy saving.

Motorcycle engine technology!

Guy Martin, the motorcycle racer, truck mechanic and energy efficient building advocate, bemoans the lack of progress in motorcycle engine technology compared to commercial trucks. He puts this down to the much tougher emissions requirements for trucks (because there are so many more on the roads) which have driven progress at a fast rate. Whilst still niche, Passivhaus has created a demand for significantly improved products and methods from the forementioned airtight boards and durable sealants, through high quality windows and doors to quieter and more efficient ventilation systems. Many of the improvements turn out to be cost neutral or even cost negative once embraced as standard. Indeed, Passivhaus designers who have embraced even better airtightness are able to reduce insulation thicknesses without compromising total heating demand.

Nick Grant and Guy Martin talk efficiency. Photo credit: J Woodroffe, North One TV

What about Heat Pumps?

So, as we move away from gas to heat pumps and a decarbonising grid some would argue that our buildings can use around 5 times as much energy for heating and still be responsible for less carbon emissions than a Passivhaus with a gas boiler. This is true and very relevant when considering how far to push retrofit for urgent carbon reduction.

However, if we can achieve Passivhaus levels of energy efficiency through clever design, pretty much for free and with wider benefits [Ref 4. PHT] then why not? Also, with electricity costing about three times as much as gas, with a COP of around 3 for our heat pump the economic arguments have hardly changed.

Or PV?

Another argument is cheap PV. This is a good match for summer cooling but if we are to move to a fully renewable future there is no alternative but to reduce heating demand in the depths of winter. A thermally-stable building is a great match for tariffs that reflect hour-by-hour energy availability and so cost.

Our work is done, or is it?

So, if excellent airtightness and quality ventilation were to become the norm for the reasons given, and if the performance gap that Passivhaus set out to close can be eliminated by regulation or consumer pressure, then we can reconsider the cost benefit of Passivhaus against that benchmark. Until such quality becomes the norm, we have a proven way to deliver high quality, comfortable, economic and future proof buildings that will not require retrofitting in a few years.

In conclusion, Passivhaus is still (unfortunately) relevant!

2018 timber-framed newbuild home in Powys, designed to the Passivhaus standard and achieving an airtightness of 0.12 ach @ 50 PA with a build cost for the airtight shell estimated to be £1200/m.2 Space heating and hot water is provided by an air source heat pump, with radiators. Total energy consumption (electricity), including the freshwater borehole pump and workshop building, circa 3,100 kWh/year which equates to 20.6 kWh/(m2.a). Image credit: 21 degrees. Further info here.

Refs:

- AECB Webinar, Sally Godber. Link

- Farren P, Howieson S, and Sharp T. Building tight - Ventilating right? How are new air tightness standards affecting indoor air quality in dwellings? August 2013 Building Services Engineering Research and Technology. Link

- Building standards - ventilation guidance: research Published 3 May 2023, Directorate Local Government and Housing Directorate. Link

- PHT Benefits Guide. Link

Call to action:

Building to perform is easy if you know how – our 21 trainers, all practising professionals, will guide, up-skill and inform you through our comprehensive suite of courses:

Designers/Consultants: Bitesize | Certified Designer | Retrofit Delivery

Clients Asset Owners: Bitesize | Build to Perform Introduction (available 2026)

Site Managers and Contractors: Build to Perform Introduction | Intermediate (available 2026) | Certified Tradesperson | Retrofit Delivery

None of these feels like the perfect fit! We offer bespoke training too.

Contact our support team to discuss your specific needs and we'll create something tailored for you. CONTACT US